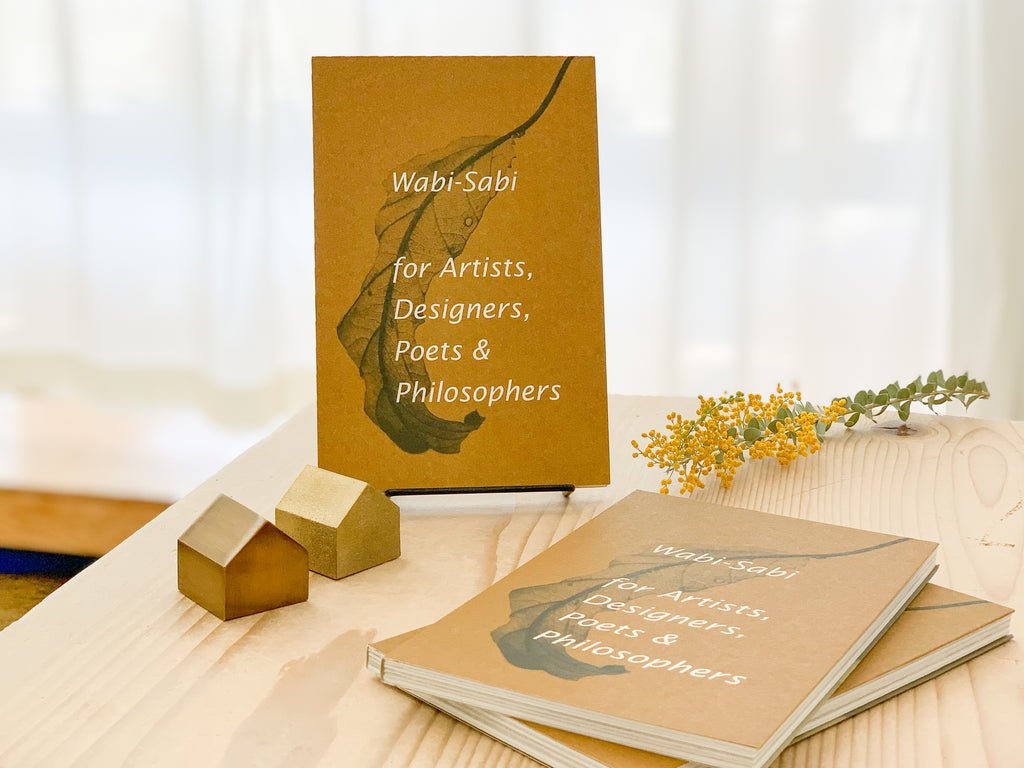

For many years, we've had Leonard Koren's book, Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers, at the corner of our front counter, greeting customers as they walk in. This concise yet rich book explores the most ephemeral of Japanese aesthetics - wabi-sabi. We wanted to connect with Koren - a long time artist, aesthetics expert, and the author of several books - to dive deeper into his understanding of wabi-sabi and its relevance to this current moment.

Ruby Zuckerman: For many of us, Covid-19 has been one of the most disruptive changes to daily life that we have ever experienced. As a "comprehensive aesthetic system", are there perspectives present in wabi-sabi aesthetics that can help us cope with the grief, loss, and change brought on by Covid?

Leonard Koren: A wabi-sabi state of mind may, indeed, offer some solace in trying times like this. It works for me. Wabi-sabi is a poetic sensibility. It is about the empathy we feel with the fragile and tentative aspects of things—things primarily fashioned out of natural materials. Things that share, as we humans do, an inexorable journey towards nothingness.

Photos courtesy of Leonard Koren, published in Wabi-Sabi, For Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers

RZ: Because of the danger of gathering with others, there has been a large attempt to provide digital alternatives to connection. I love your description of how screens tend to homogenize any kind of sensory experience. Wabi-sabi is very much about sensory experience - be it through texture, smell, or even temperature. Do you think there is any way to have a digital wabi-sabi "experience"?

LK: I used to think not, but I’m not so certain anymore. Wabi-sabi is an event that occurs in the mind—as do all forms of beauty. I used to think that this magical transfiguration required an object or occurrence from the actual world as a trigger. I’ve gone over and over the logic of wabi-sabi, but now some cracks in my thinking have formed. If someone can derive what they think of as a wabi-sabi experience from a series of zeros and ones offered up in a virtual world, more power to them. For me though, wabi-sabi is still resolutely grounded in the physical, i.e., “real” world.

RZ: Is it accurate to describe wabi-sabi as an aesthetic that is transient? Can an object be classified as wabi-sabi in a certain context, and then no longer be classified as wabi-sabi once it is placed in another? For example - a humble, imperfect, stone vase that has been placed in a white-wall gallery and listed at hundreds of thousands of dollars. Or, a picture of a dark, earth-toned room that is then shared on social media hundreds of thousands of times.

LK: We make sense of things depending on the context we perceive them in. The same object may or may not be wabi-sabi, depending on the context. So in the examples you give, an art gallery and a social-media context, I guess it just depends on what goes on in a particular perceiver’s mind. Speaking for myself, if I see something on a screen that looks like wabi-sabi, I think of it as just that: something that looks like wabi-sabi. But I don’t consider it to be wabi-sabi. Wabi-sabi is more than a “look.” It is a complex of deep, resonant thoughts and feelings.

RZ: You mention how a reverence for nature is a crucial component of wabi-sabi. Do you think wabi-sabi aesthetics could ever be harnessed as part of environmental activism? Or is wabi-sabi resistant to being "used" for any kind of purpose or agenda?

LK: I don’t see why the “use” of wabi-sabi and the “appreciation” of wabi-sabi should conflict. Yes, I could imagine the wabi-sabi concept being put to good use by environmental activists.

RZ: Do you feel like you have achieved what you wanted by publishing your Wabi-Sabi books? After so many years in print, do you feel like the message you meant to share has been understood?

LK: All I really wanted to accomplish with Wabi-Sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers was to introduce an aesthetic concept I had a strong affinity with to an audience outside of Japan. I thought my readership would be very small. I was pleasantly surprised by the warm response to the book. I guess there are many of us out there looking for more sensitive, fulfilling ways of experiencing conscious existence. . . . But yes, I do run across instances of wabi-sabi reduced to a design-style de jour, even stranger, a vehicle solely for “self-improvement.” Yet, that’s the way our culture works: Fertile ideas, whatever their provenance, are transformed by entrepreneurial types into all all manner of commodities. It used to cause me grief. But I’m over that now. I accept that this is just the way things are.

RZ: As an artist and writer, does wabi-sabi come into play in your particular practice? What does your creative practice look like right now, and are wabi-sabi aesthetics a part of it?

LK: Synthesizing the wabi-sabi concept, and then writing and designing a book about it, was an amazing experience. Before I embarked on the journey, I had no idea that I would enjoy rendering an opaque, nebulous aesthetic concept into an easy-to-understand paradigm so much. I was so inspired by the process that I subsequently went on to explore other arcane aesthetic notions as well. My most recent book, Musings of a Curious Aesthetics, chronicles what led up to Wabi-Sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers, and my work that followed. If you’re interested, I suggest reading the book.

Portrait of Leonard Koren by his thirteen year old son, published in Musings of a Curious Aesthete

RZ: You yourself are not Japanese, however, you have spent many years living in Japan and are well known as an expert on Japanese aesthetics. Do you think your position as an outsider helps you to break down a concept that seems particularly ephemeral? How has your identity as an American helped or hindered your wabi-sabi research?

LK: Yes, my position as an outsider was essential to the task of getting to the root of wabi-sabi-ness. Japanese scholars and cultural authorities, hesitant to roil the academic and socio-political waters, stayed away from the task. This left me, an an artistically and analytically inclined foreigner—I lived in Japan on and off for twenty years—a glorious field of exploration all to myself.

RZ: Any recommendations for those interested in further research about wabi-sabi?

LK: Spend time in Japan, particularly Kyoto. (Tokyo is great, but it’s more preoccupied with modernity.) I think going alone, at least for the mind-altering first trip, is best. Kyoto’s shrines and temple complexes are a must. Walking around the older neighborhoods and breathing in the air is also essential. I would also recommend reading The Book of Tea by Okakura Kakuzo. It was written in the English language by a Japanese polymath at the beginning of the 20th Century. And last, but not least, get yourself invited to at least one Japanese tea ceremony. In the Los Angles area this should be fairly easy to do.

Wabi-Sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers is available for purchase on our online store.